Like historians, people on the internet talk to each other in disparate threads. They borrow, interrogate, re-hash, and complicate ideas, in the process creating discourses that endlessly evolve. This process of repetition also legitimizes the subject at the heart of the conversation, adding meaning to every new interpretation. That is my way of telling you I’m going to talk about Booktok.

I felt for some time that I should talk about Booktok, at least on Substack. Notwithstanding the imminent demise of the app as a whole, this subcommunity has been the inspiration for various articles on whether Booktok is ruining literature, whether bookshelves are displays of wealth, and the never-ending cycle of anti-intellectualism. These things were entertaining but seemed like a train that had run its course. That was until last week when I watched a video from Maxwell (@welldonebooks) that sparked my curiosity and dovetailed with various threads of historiographical thought laying dormant in my Substack drafts. Immediately he begins with: “I don’t think every book has to bring you joy…and that if you’re not enjoying a book that its automatically bad.”

The line of thought reflects evergreen questions often at the center of literary discussion: what is the function of the book for a reader? Is reading for learning or enjoyment? And if it is for enjoyment, even partially, do books have a responsibility to make us feel good while reading them?

I won’t pretend to be a literature scholar and investigate it from that perspective, but I do think there is something deeply American about assuming that things exist to comfort us or make us feel good. Because that is at the heart of this whole thing, right? The assumption that if reading is our hobby that books should comfort us rather than unsettle us. What is particularly interesting is that this dialogue is gaining traction at a moment where intense political polarization, rising nationalist movements, and dramatic economic shifts penetrate our daily lives.*

*Fair warning but this newsletter will be very U.S. centric. That is not me saying that all Booktokers are American, more so that there is a preponderance of American cultural, business, and political influences when it comes to dialogue on Booktok But also yeah, a lot of booktokers are American.

Indeed, some of the most salient conversations on BookTok tend to emanate from or converge with the question of “are books political?”. Shortly after the results of the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election, in which Donald Trump secured an overwhelming win, a slew of videos were posted from bookish creators compelling fellow users to “leave politics out of Booktok,” a popular one being from a now deleted account called “Kenzies Book Nook”. This was followed by a more popular wave of reaction videos pointing out political discourse within and around fiction titles (see popular stitches here, here, and here).

Four days after the election, mentions of an “unfollow list”, a list of authors who were “confirmed” to have voted red in the U.S. presidential election, began circulating. The function of list was to inform audiences of authors they should not support by centralizing information about their views into a quickly digestable format. The intention of these literary or cultural lists (and trust, this is far from the first) may be well-meaning but the implications often murky. The most obvious implication is that via this rendering, the acts of reading, purchasing, recommending, or discussing books become flattened. If you read books by bad people, that also makes you the reader, a bad person therefore we should feel uncomfortable consuming them.

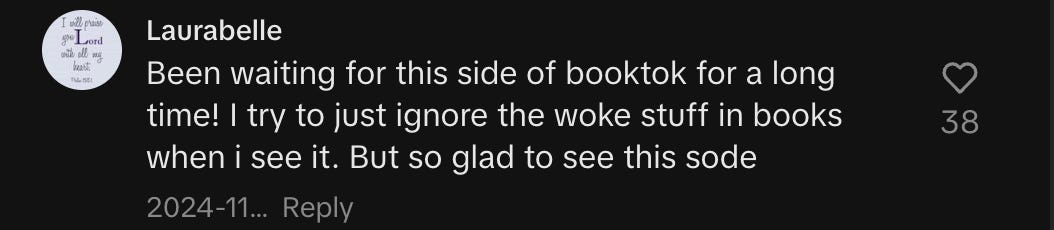

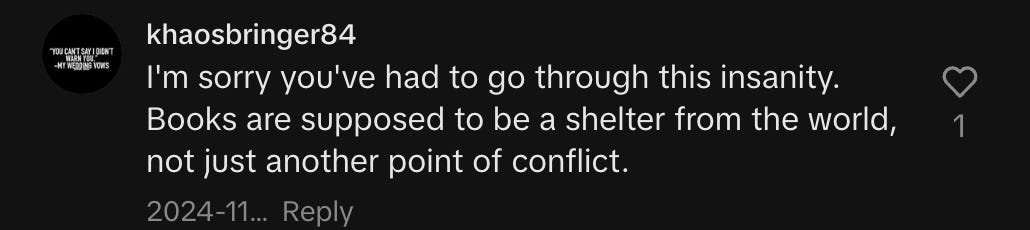

Videos and comments from conservative users began circulating in response, urging others to “just let me read what’s makes me happy.” Another asserted that “we escape to our books for peace and self-growth.” In a video with over 40,000 views and 500 comments, user amberpatriotmom expressed heartbreak over her favorite authors condemning MAGA followers, stating in a text overlay that she just wanted to get “lost in their books” without having to think about their political views. Comments on the video echoed the sentiment, one person stating they “just try to ignore the woke stuff” and another that “books are supposed to be a shelter from the world.”

Such comments reflect a common rebuttal that books, particularly fiction, should function for the reader as “escapism,” either from the mundanity of the politics of daily life or the depravity of it.

Interestingly, this concept is one shared across the political aisle. Users who verge left or center-left suggest that the act of reading provides an outlet from anxieties about the state of the world. Popular videos that appear under the search tags “escapism Booktok” or “escapism reading” frame the activity in terms of mental health, in turn pathologizing the act of reading (see this one with over 1.2 million views). Others are more explicit in their political leanings, one such post featuring text overlay states “people not understanding that reading is a coping mechanism for living (especially in the U.S.)”. Tim Walz, the internet’s center Left “papa”, also echoed this sentiment in a recent video posted by his daughter.

This comment was the top liked on the first linked video in the above paragraph. In their main profile they outwardly address national politics and voiced support for Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election.

Users at varying points of the political spectrum differ on the extent of escapism’s relationship to reading, though they engage with it nonetheless. For those on the left, escapism is a tool for distracting oneself from the hardship of daily life, usually directly or indirectly linked to the political or economic climate. For those on the right, escapism is often invoked in response to valid critique of authors or themes in their books (this is a Substack so you’ll have to give me grace for painting in broader brushstrokes).

To be clear, this is not me doing moral relativism and my goal is not to “gotcha” users on the left. There is a material difference between them and users who employ the escapist narrative to abdicate their sense of responsibility towards others and towards meaningful political engagement. Nor am I suggesting that escapism is a totally unhealthy or abnormal approach to literature or that those who read for “escapism” only read in that way (reading is an amorphous hobby as we all know). The more interesting part of this conversation, in my view, is the why? Why, if we are so politically divided, does escapism “work” for everybody?

The common denominator seems to be one rooted in the perception that the act of “escape” entails distancing oneself from something unpleasant, towards something comforting, at the same time reflecting a profound, shared anxiety about the future of the country. The something unpleasant in both cases is political reckoning. Escapism then becomes a useful tool in the readers arsenal for insulating oneself from reality and in turn, depoliticizing the act of reading under certain, very specific circumstances.

The above comment illustrates in real time the work that “escapism” does for those looking to depoliticize their reading. Books are designed as entertainment, they are meant to “shelter” us from reality, not force us to confront it. If a book does have transformative power it is at the individual level, not the political one.

Other forms of depoliticization are more nuanced. The comment below is reliant on the idea that “challenge” and “comfort” are inherent qualities of genre itself. It suggests that books have total authority over our reading experience of them and by extension, that books exist for a specific, static purpose. These examples show that escapism is both pervasive and fluid. It is used widely but unevenly.

This is the way in which most of us conceive of the act of “escapism”, what Robert Heilman in 1976 deemed a “little highbrow phrase for a manifestation of lowbrow spirit.” Heilman argued that the escape concept had gone through an epistemological shift in the 20th century from one that broadly understood the act of “escape” as a striving or an adventure, to “escapism”, the habitual act of distraction or running away. Prior to mid-century, escape from discomfort could not have been conceived as an option. It was American affluence, Heilman posited, that “diminished tolerance” for the steady toil and discomfort that had characterized people’s lives up until that point.

“Abundance is a relaxation of bonds; it begins to make all bonds…seem arbitrary rather than in the inevitable nature of things.”

More succinctly, prior to the New Deal, most Americans’ lives were hard. There was no expectation or sense of entitlement to comfort and therefore there was no impulse to seek it out. Notions of thrift were also deeply embedded in American culture. That one should prepare for hardship was a shared inevitability, rather than a cultural or political anxiety. There could be a sense of wonder about the potentialities of the world but not in a way that suggested comfort was achievable or owed.

Others have echoed something similar to Heilman. Paul Hollander stated in his collection of essays on adversarial culture that “estrangement” (the inability to establish harmony within ourselves and with the outside world), was linked more acutely to American culture. “High expectations as to the perfectibility of social institutions and the possibility of maximizing the…contentment of individuals” led to impossibly high standards that justified greater discontent. John Limon supposed that “if escaping the unlovableness of your condition is the essence of escapism, if the love of your condition becomes unconditional, then escape is detention.” Escapism, as the repeated act of distraction, requires a thing to be distracted from in the first place. It requires an “obliviousness to alternatives” and in doing so binds us further to “evil” than it does in liberating us from it. We are driven deeper into escape as the promise of societal perfectibility becomes less a promise than an illusion.

Honestly, Limon’s position is a bit stark for my taste. I’m not sure if escapism solely within the domain of hobbyist reading constitutes a prison. The bigger issue I think with escapism is its intersection with U.S. consumer culture. Specifically, the ways that consumerist tendencies mask themselves as meaningful political power. The shared inclination to seek out comfort speaks to this larger culture of comfort we have in America, one which proclaims that comfort can be individually bought and consumed. This was what Lizabeth Cohen referred to as a “consumers republic.”

U.S. culture shifted drastically in the post-war era from one that encouraged thrift to one that abolished it. In the consumers republic, the post-war order was defined by a concerted effort to impress upon Americans that “mass consumption was not a personal indulgence” but rather a civic responsibility that could effect the security of the country through industry and national markets. Marita Sturken, though writing about tourism in her book Tourists of History, talked about the role of comfort objects in Americans’ political lives. Sturken uses objects whose form tends to share a direct correlation to their function (teddy bears, snow globes, etc) and it needs to be noted that books perform a more capacious labor in our lives. However, the discourse around escapism and books on Tiktok reflects the idea that like, teddy bears, books have the potential to be comfort objects, but who or what determines that?

What fascinates me most is that those books (or genres of books) which we tend to assume are escapist comfort objects also tend to be seen as “kitsch-y” - somehow reflective of lowbrow, mass consumer culture. There is a tendency to see them as having a flattening and commodifying effect on daily life because they are kitsch and kitsch is naive, it exists in a vacuum that demands nothing and discourages inquiry.

Fair enough, but as Sturken argues, this conception belies the more complex role kitsch plays in our lives. “The mass culture critiques of kitsch were, in effect, criticisms of lower-class taste, defining it as uncultured. Yet in the contemporary context of mixing modern and postmodern styles, ironic winking and the cross-class circulation of objects, such critiques carry little meaning.” It is easy to criticize genres, books, and readers we deem as “kitsch” because in the process it says something about how we choose to spend our money. It says something about who we are and our taste and our discriminations.

It is prudent to remember that ideas about our own security and comfort are bound up in our purchasing power, which is rapidly declining. In 2022, Bank of America estimated that about 35% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck and now, less than three years later that is up to 50%. Homeownership rates among younger Americans are lower now than 30 years ago. Our consumerist culture is chaffing against neo-liberal markets, shrinkflation and rising costs of living, making it harder to consume the items we seek comfort in. Books on the other hand, are both products to be consumed and pieces of media to be consumed. It is less about how the act of purchasing the books reflects back on us than about which ones we consume, how we do it, and how we perform that consumption for an audience.

The issue with this form of consumption is that it does not take into account the fluidity with which “kitsch objects”, may move between high and low sensibilities. Escapist books and genres are kitschy, apolitical, and comforting - but above all they are static. Not only do they meet us where we are, they are diametrically opposed to challenging books. We rely on them as a barometer for our own discernment, simultaneously reinforcing our sense of self and displacing comfort. Because to assume that books perform comfort labor in our lives is also an assumption that comfort is somewhere else. That through our consumption of such media we will be comfortable and safe in a world that is anything but.

What I think is most fundamental to our reckoning with escapism is first an acknowledgement of its symbiotic relationship to our political culture. Second in this is a renewed look at the assumptions we make about books as both objects and art. I think there is a tendency to collapse form (genre) and function in ways that harken back to Sturken. This approach makes books static, material items that serve primarily to reflect ourselves back onto us rather than as dynamic pieces of art capable of moving us from one place to another.

And let me be clear, I don’t think the solution here is to throw comfort out of the window. I don’t think its wrong to want to be comfortable (no matter how much my WASPish cultural DNA rebels against that idea), nor do its wrong to feel comforted by a book.

The place where I think it becomes messy is when we subscribe to the belief that books as objects possess wholly and intrinsically a certain characteristic, precluding all others and dispossessing the reader of any agency in their interaction with the art. What I want to say is that we should be more malleable, more willing to meet books where they are. To acknowledge that our items may be “doing work” in our lives but that we still need to animate them. To acknowledge that escapism has a history longer than booktok and is a phenomenon tied deeply to a national desire for comfort that we all subscribe to, whether we want to or not.

With the potential demise of the app in just a few days, I wondered whether this article was worth rushing to finish. Its not exactly a eulogy nor is it a reminiscence on times past. Maybe its some backward, denialist attempt to will the app’s continued existence? Maybe I’m just avoiding doing work that could get me closer to my degree, who knows!

Regardless, if the end times are really nigh and if I haven’t said it enough, thank you for being here. The app, for all of its drama and issues, is a net positive in my life. I’ve learned a lot about myself and about books and about publishing that I would certainly not have otherwise. I also wouldn’t have had the chance to meet some of the kindest, funniest, smartest people in New York and for that I am grateful!

I’ll do my best to regularly update the Substack, perhaps with more book reviews, recommendations, wrap ups, etc. In the meantime, thank you for reading :)

Sources:

Cohen, Lizabeth. A Consumers’ Republic : The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. First Vintage Books edition. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2004.

Heilman, Robert B. “Escape and Escapism Varieties of Literary Experience.” The Sewanee Review 83, no. 3 (1975): 439–58.

Hollander, Paul. The survival of the adversary culture: social criticism and political escapism in American society. Transaction Publishers, 1988.

Limon, John. "Escapism; or, The Soul of Globalization." Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture 49, no. 1 (2016): 51-77.

Sturken, Marita. Tourists of History : Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Brilliant

This was so, so good. In awe. 🧍🏻♂️ here’s me waiting for more posts from you on substack in the future